Deng Fei started up several campaigns using Weibo (a Chinese Twitter-like social networking site with Facebook elements) targeting at helping children and caring for nature, which includes the Free Lunch for Children, the Anti-Child-Trafficking Campaign, the Anti-River Pollution Program, the Free Healthcare for China’s Rural Children and the Children Protection Scheme. Among these, the most influential is the Free Lunch for Children program. By the end of 2017, the program has raised 368,59 million yuan, offering free lunches to 251,359 children in 931 country schools.

Deng Fei, the man behind these successful campaigns, started his career as an investigative journalist. Realising the people’s power in the new age of Weibo ― the social media where information becomes readily communicated by all and accessible to all, he grabbed the opportunity to make a difference in the Chinese society. In 2011, he gave up his 10-year career as an investigative reporter and continued his life as a philanthropist. Now he has over 5 million followers on Weibo, helping him to make his philanthropic programs known to more.

For his pioneering role in journalism, social media, and charity, He was awarded Davos Global Young Leaders in 2014. He graduated from the EMBA degree from China Europe International Business School (CEIBS) in 2015.

A Watch Dog: Anti-Child-Trafficking Campaign

In the field of journalism, investigative journalists are described as watch dog, being the media that scrutinizes and monitors social issues., In 1998, Deng Fei started as an intern in a news agency as a second-year university student. This was the kick-off of his investigative journalist career. From then on, he has written over 100 reports to reveal the truth. Most of his subjects were about the operations of government agencies and the vulnerable and disadvantaged groups whose voices are not heard in the public.

In 2003, he joined Phoenix Weekly, a Hong Kong magazine which provided him with an even larger platform. Many influential reports were produced in those years like Killing Yangzong Lake, Lung Disease in Zhouzhuang, and Children Trafficking Chain in South China. During this time, he also made a big difference by organising a group of more than 500 reporters and editors to cover the stories in the countryside of China. This group contributed a lot to his great success later as a philanthropist.

But in the relatively small journalism circle, the man never truly made his name across the country until the Anti-Child-Trafficking Campaign he initiated on Weibo. In his words, he found himself “confronted by a new era” ―the age of Weibo in 2009. In 2010, he posted a photo of a missing boy who was kidnapped and trafficked in 2008 with the caption “Will Weibo make a miracle? Please help the father to find his missing boy.” It was “retweeted” 5665 times. Four months later, the boy was found by a Weibo user in a village in Jiangsu Province.

Witnessing the power of Weibo, Deng Fei believed it would be the most useful tool to combat children trafficking, as each user could get access to the photos and information of missing children. Under his initiative, people across China made joint effort with the police to form a huge network to fight against children trafficking. It directly led to policy changes against human trafficking in the Central Government’s Ministry of Public Security.

A Builder of Society: the Free Lunch for Children Program

Deng Fei’s book

Deng Fei’s book

In 2011, he realized while as a journalist he could make a difference by influencing readers through his reports, he could take action, with the help of Weibo, to address the problems. “China is not short of people who write articles,” he said in an interview with New Express, “but people who take action.” So he decided to shift his focus from constructive scrutiny to constructive transformation, and became more involved in philanthropic programs.

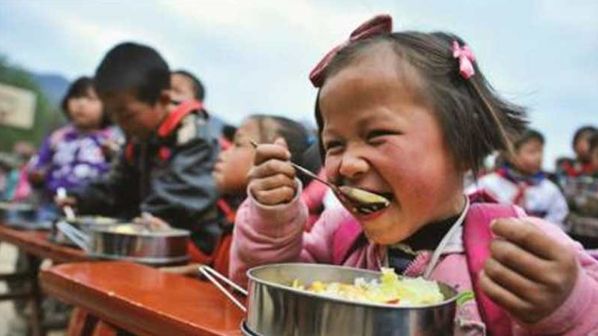

The turning point was the Free Lunch for Children program. In 2011, he met a rural teacher, who told him that there was no canteen and that many of her pupils went hungry during their days in school. The teacher felt guilty when she took out her lunchbox every day. This caught Deng Fei’s attention. Half a month later, he visited the village schools in Yunnan and Guizhou Province together with a group of journalists, and found the children going without lunch during the day. As most schools in mountainous areas have no canteens, they could have nothing but water before the school was over. Cold potatoes or corns were sometimes the better options.

This led to serious malnutrition. One survey report, published by China Development Research Foundation under the Development Research Center of the State Council, showed stark differences in nutritional conditions of Chinese students in under-developed areas. According to the report, children in the poor areas of the central and the west of China suffered from serious malnutrition. Of all students surveyed, 12% showed signs of developmental retardation and 72% would feel hungry during classes. The male and female boarding students were respectively 10 kg and 7 kg lighter, and 11 cm and 9 cm shorter below the national average for rural students.

To make things worse, as rural people flock into cities in sought of better jobs over the last three decades, the rural population, once boasting one billion, shrank gradually. As a result, rural schools have been reorganized and smaller ones were merged or closed. It is no longer unusual for students of the more far-flung areas to walk two or three hours to and from school. In those areas most kids are not able to come home for lunch.

Deng Fei, together with China Social Welfare Foundation, 500 journalists and dozens of mainstream domestic media outlets, launched a public fund-raising campaign to provide free lunches to the children in those areas. Prompted by his action, several hundred more journalists wrote about the issue. The photos he posted of hungry children on Weibo were spread far and wide. His followers on social networking such as Weibo and Tencent continued to send donations to a bank account he had opened. Within six months he had raised 3.7 million yuan from individual donors who knew his reporting work and trusted him with their money.

The challenges approached as money kept pouring in. Rapid expansion led to the question of how to monitor funds and ensure that schools are spending the money on food for students. As some Chinese charities were confronted with increasing public mistrust, transparency was a huge task for Deng Fei and his team. Again, Weibo was applied as a tool of accountability and scrutiny. First of all, each participating school were required to publicly post its weekly expense reports on Weibo. Secondly, his team worked with local government, media, non-governmental organisations and parents to oversee the accounts and visit schools to ensure the children were being fed properly. Finally, the charity’s two million followers on Weibo could monitor schools’ online accounting and travelers were encouraged to be “mystery guests”. Anyone could report by phone or Weibo if the lunch wasn’t up to the standard or any irregularities came to light. Since this was initiated, there was zero incident in food safety or fund safety. The online and offline tools were proved to be trustworthy.

Thanks to the transparency, the program made significant impact throughout China. It was listed on the official website that by the end of 2017, the program had raised 368,59 million yuan, offering free lunches to 251,359 children in 931 country schools. Indirectly, his efforts led to the Central Government’s action. In October 2011, the former Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao announced it would allocate 2.5 billion yuan for a “nutrition improvement plan” to provide a basic lunch to 26 million rural school children.

The Extension of Free Lunch: Love from Australia

The Free Lunch for Children program has had a huge impact in China and the world, leading to the partnership with other foundations. Australian China Education Foundation (ACEF) is one of them. Established in 2014, the Australian not-for-profit organisation aimed at providing direct financial assistance to children in poverty-stricken areas of China in completing their education up to year 12 through one-to-one sponsorship. In 2015, ACEF partnered with the Free Lunch for Children Foundation to start the “Free Lunch for Children, Love from Australia” program. After raising the designated fund, ACEF partnered with the Free Lunch for Children (China) in operationalizing the program, which includes selecting the school, constructing the kitchen, hiring the cook and so on. The ACEF Free Lunch operation began in May 2016 at Donggou Primary School in Gansu Province. ACEF raised $51728.60 Australian dollars as the fund for the Free Lunch for Children Foundation. At press time , the program donated more than ¥250,000 yuan to offer lunch for 97 students and teachers at Donggou Primary School.

In October 2017, ACEF’s Vice President Wang Yongfu paid a surprise visit to Donggou Primary School, without informing the school. To his delight, he found out that the kitchen was neat and clean, and the food was nutritious with good flavour. The children were satisfied and happy.

In April 2018 ACEF will embark on fund raising initiatives for the next two years and has invited Deng Fei to join us in Melbourne. The donation of each donor was set at $198 Australian dollars. Please support ACEF and Deng Fei in this meaningful event.

In an interview with People’s Daily Online, Deng Fei was asked about his identity. He said, “I am a citizen. You can identify me as a journalist, or a volunteer in charity, never mind. But no matter who we are, journalists or volunteers or citizens, these things are what we should do. We have to spread the right voice, and let more people know the truth.”

The “Free Lunch for Children, Love from Australia” program reflects the same spirit in all of Deng Fei’s efforts, who is working on the “Free Healthcare for China’s Rural Children”, continuing his role as a builder of the Chinese society.

From a top investigative journalist in China to a influential philanthropist, Deng is defining charity in this new media era. Deng Fei’s charity can provide voices to individuals, be supervised by society, and share love with boarder people.

206/566 St Kilda Road, Melbourne, 3004

206/566 St Kilda Road, Melbourne, 3004